When LGBTQ+ History month was first celebrated in 1994 it was a very different world for us.

The number one rated show in the United States was Seinfeld; Ace of Base, All-4-One, and Boyz II Men were at the top of the charts for music; the box office hit at the theatres was The Lion King, followed at a very distant second by Forrest Gump. This was before Will & Grace and right after Pedro Zamora graced us with his presence as an openly gay participant in the Real World.

It was 21 years after the DSM removed homosexuality as a disorder and Matthew Shephard still had 4 more years to live. Bill Clinton’s administration had just passed the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy in the military the previous December and gay sodomy would still be criminal in Texas for the next 9 years.

RuPaul just released Supermodel the previous year, and was growing into his own after being an extra in the B-52’s Love Shack video; it would still be three years before Ellen Degeneres would come out on her sitcom.

Rave and club culture was at its height, with everyone wearing fantastical costumes of every shape and color, and in New York, Michael Alig reigned supreme with his Club Kids.

Many in the community were still reeling in the aftermath of the AIDS crisis in the 80s, over the course of which we lost a whole generation of would-be elders to a disease that was notoriously, appallingly ignored by Ronald Reagan’s two-term administration. Safer sex campaigns were rampant and, for a time, AIDS was synonymous with “gay” and nothing else.

This was the world in which the first openly gay public school teacher in Missouri, Rodney Wilson, started Gay History month–eventually to be known as LGBTQ+ History Month.

I didn’t know queer history growing up.

What I did know was that gay people were made fun of and that gay people were the ones that got AIDS. I also knew that I was attracted to boys but didn’t want to admit it because of the previous two statements. Something else I thought I knew was that I hated history. The focus was on subjects that felt foreign, old, and irrelevant. We talked about dates and names but never really about desires, motivations, or the complexity of the human experience. Why should I care about the actions of dead people that didn’t look like me, act like me, or have anything in common with me?

It wasn’t until college, living on Capitol Hill in Seattle, that I was introduced to the concept of a community with a proud history, one that wasn’t broken down, tired, or defeated but one that had fought and survived through impossible odds to still bloom in the most hostile of atmospheres.

I remember going into the gay bookstore and seeing shelf upon shelf of books about people like me. There were our racy romance novels, our poetry and art, treatises and manifestos on queer theory, biting commentary and wit put to paper… but amidst all of those were books were tomes of a more ancestral timbre; our histories laying out a legacy for our present and future. I had always admired Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. because it was the only part of history that made sense to me or that seemed to matter. But now, in this bookstore, I found the words of Eric Marcus and Leila Rupp teaching me about Harry Hay, the Mattachine Society, the story of Stonewall, and Harvey Milk. I didn’t dislike history–it’s just that until this point I didn’t know any that was written for me, and now I wanted more.

Suddenly, we mattered. I mattered.

We are now in the year 2021. The science fiction media during the early 1990s referred to the period we’re now in as the “not so distant future.” In California today, not so distant from the young man at that Seattle bookstore in the mid-90s, we are only beginning to understand what it means to teach the next generation of queers our history.

What a difference it would have made in my formative years to have had known that queerness was neither a phase personally or societally. The number of heartaches and the weight of guilt that could have been avoided if I had only known there were others like me, and that I was descended from a long line of beauty, strength, and rebellion.

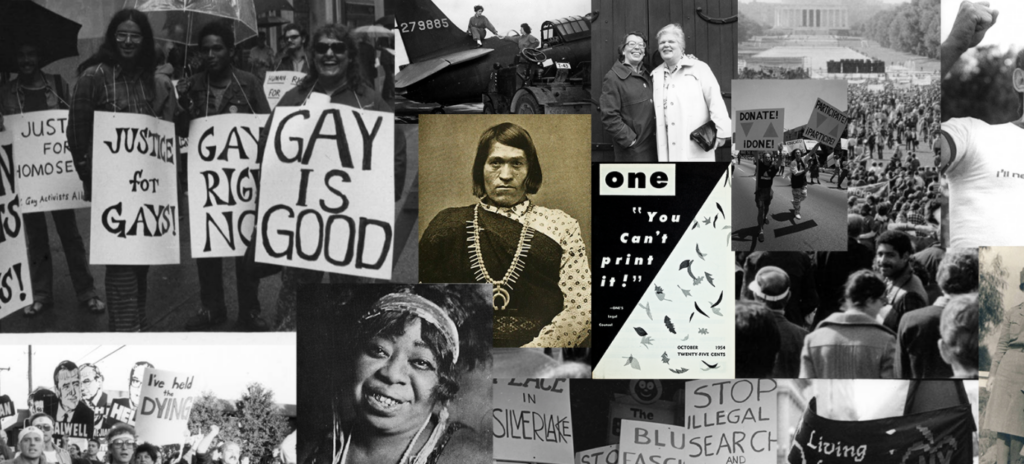

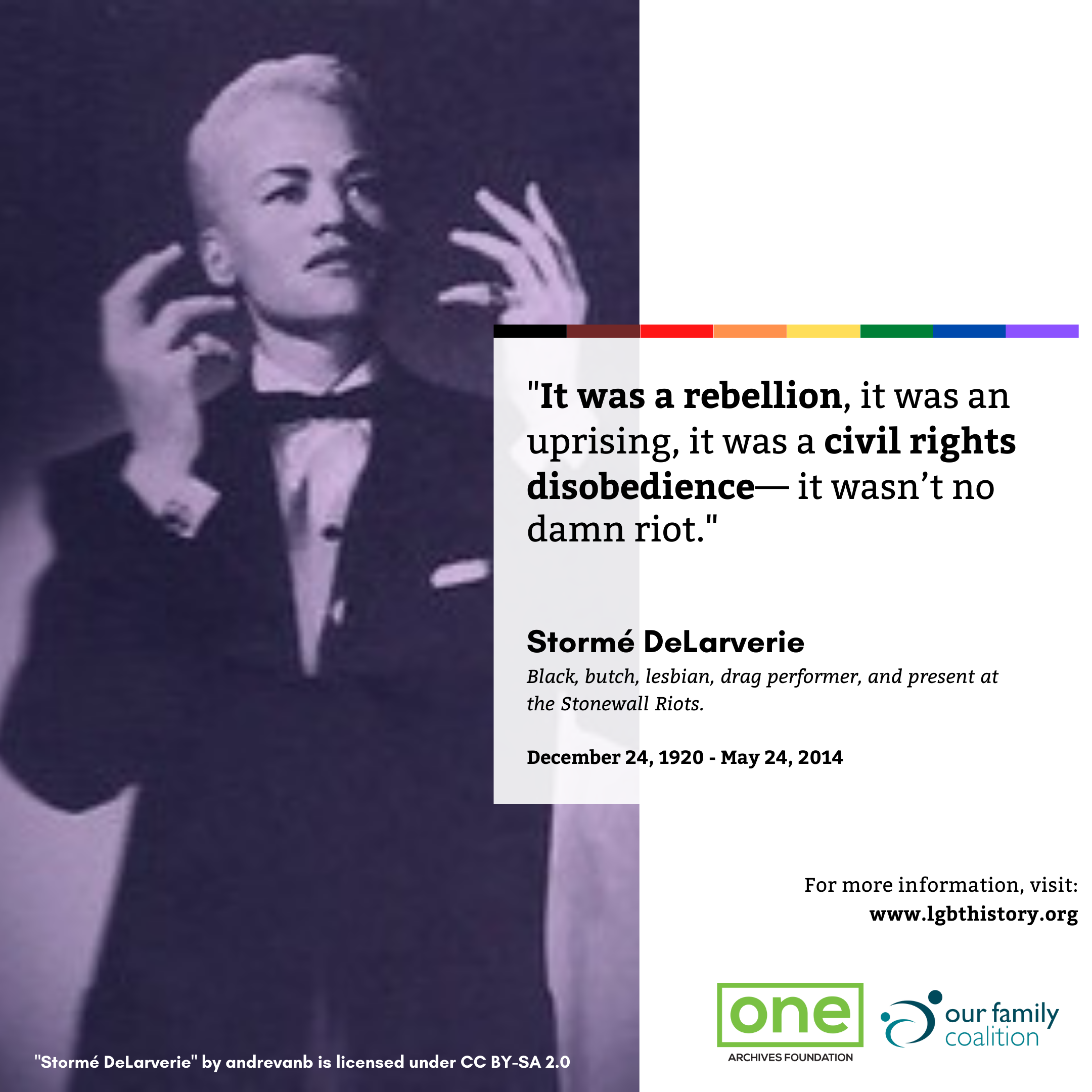

As we push for a more honest and representative history, one that is more brown and queer and critical, we must also take the steps to celebrate in order to solidify that history in our nascent memories. Sadness will not be the sole note struck by our community. In this vein, for this LGBTQ+ History Month, Our Family Coalition is joining with ONE Archives Foundation to present 31 days of queer vibrancy, queer legacy, and queer hope.

As we push for a more honest and representative history, one that is more brown and queer and critical, we must also take the steps to celebrate in order to solidify that history in our nascent memories. Sadness will not be the sole note struck by our community. In this vein, for this LGBTQ+ History Month, Our Family Coalition is joining with ONE Archives Foundation to present 31 days of queer vibrancy, queer legacy, and queer hope.

We invite you to join us and learn about those that came before us, those that are still here, and those that we will become. Every day during the month of October we will be releasing an infographic featuring historic and iconic members of our community each linked to a resource or lesson plan where you can learn more about our queer family.

I was once asked why I worked so hard on queer history and why it was so important to me, and my feelings on it have not changed. I grew up afraid of becoming a joke or a casualty, but my kids will know that their uncle is more than a punchline or a punching bag. My kids, who are now in first and third grades, will not know a time when they didn’t learn about queer people in their classrooms.